- Home

- Rebecca S. Buck

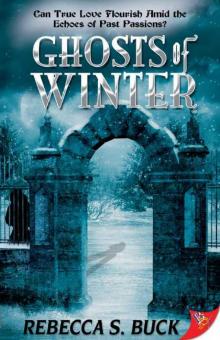

Ghosts of Winter

Ghosts of Winter Read online

Synopsis

Can Ros Wynne, who has lost everything she thought defined her, find her true life—and her true love—surrounded by the lingering history of the once-grand Winter Manor?

When Ros unexpectedly inherits Winter Manor on the condition that she oversee the restoration of the remote and dilapidated house, it seems the perfect place for her to retreat from her recently failed relationship, the death of her mother, and the loss of her job. But Winter Manor is not entirely at rest. The echoes of its past reach forward into the present, and Ros’s life is perceptibly shaped by the lives—and loves—of the people who inhabited those rooms and corridors in the centuries before her.

Then Anna arrives. The architect—with her designer clothes, hot car, and air of supreme professionalism—is at first an unwelcome, if necessary, intrusion. But as Ros learns Anna’s truths, she finds solace from her past losses in their developing intimacy. And when their love is threatened, Ros must decide whether her own ghosts will forever define her, or if she can embrace her life for what it is—past, present, and future.

Ghosts of Winter

Brought to you by

eBooks from Bold Strokes Books, Inc.

http://www.boldstrokesbooks.com

eBooks are not transferable. They cannot be sold, shared or given away as it is an infringement on the copyright of this work.

Please respect the rights of the author and do not file share.

Ghosts of Winter

© 2011 By Rebecca S. Buck. All Rights Reserved.

ISBN 13: 978-1-60282-514-7

This Electronic Book is published by

Bold Strokes Books, Inc.

P.O. Box 249

Valley Falls, New York 12185

First Edition: April 2011

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

This book, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without permission.

Credits

Editor: Ruth Sternglantz

Production Design: Susan Ramundo

Cover Design By Sheri ([email protected])

Acknowledgments

Ghosts of Winter was written over a time of transition in my life. As a result, there are very many people—friends and family—I would like to thank for your love and support, far too many to name you all here! I hope you know who you are and how heartfelt my gratitude is. Some of you have always been in my life, some of you I’ve had the pleasure of meeting in this last remarkable year. You help me create a world in which my imagination can be unleashed. Thank you.

There are some people I simply must mention by name:

Ruth, you worked as hard on Ghosts as I did. Thank you for every moment of your time and all of your amazingly skilled input. It is a privilege to work with you to make the best book we can and I consider myself incredibly lucky.

Radclyffe, thank you for being the inspiration and guide behind all that Bold Strokes Books is and will be, and for letting me live my writing dream.

Sheri, this cover is stunning. Thank you so much for making my book beautiful.

Lynda, thank you, your help with the yoga was invaluable!

And to everyone else at BSB too: the feeling of being part of a team is so incredibly special and my words only become that most magical of things—a book—because of you. Thank you.

Raych, I honestly don’t think this book would be what it is without you. Thank you for all the words we’ve shared.

Lindsey, writing can be a solitary thing. Sharing my lonesome writer’s world with you makes it less daunting and much more fun. Thank you!

And once more to those I haven’t named. I take no one for granted. Thank you.

Dedication

To the ghosts. Those of history and of our own lives.

May they inspire us, teach us, and remind us

of our common humanity.

Timeline: Winter Manor and Its Inhabitants

1746 – Lord William Fitzsimmons Winter inherits an old Tudor manor house from his father, has it demolished and rebuilt in Palladian style.

1751 – The new Winter Manor is complete. Lord William invites his friends to visit in June.

c.1780 – Lord William dies with no children. Winter passes to his cousins, the Richmond family.

1848 – Though his father still lives, Edward Richmond moves into Winter, with his wife Kitty and his children, Francis and Catherine, then aged nine and five.

1862 – In autumn Maeve Greville comes to tea at Winter and meets Catherine for the first time.

1863 – Maeve returns to Winter in spring, as Francis Richmond’s fiancée.

c.1865 – Catherine Richmond drowns in the river in Winter’s park.

c. 1893 – Francis Richmond inherits Winter from his father. He does not marry and has no children.

c. 1900 – Francis Richmond dies, Winter passes to his distant cousins.

1917 – The legitimate male heir to Winter, Wilfred, is killed in World War I.

1925 – Simon, master of Winter, dies with no living children. Winter passes to his sister, Mary.

1926 – Mary, mistress of Winter, dies and her daughter, Evadne Burns, inherits the house.

1927 – Evadne Burns has a liaison with John Potter, the neighbouring farmer, and falls pregnant. That summer Evadne invites her school friends to Winter for a reunion. Later in the year, John Potter marries May Shipley, the housemaid. Their daughter, Maggie Potter, will eventually inherit her father’s farm.

1928 – Evadne gives birth to a baby girl she names Edith, Edie for short.

1930 – As a result of the global economic meltdown, Evadne is forced to abandon Winter for a smaller house and find work.

1940 – Winter is requisitioned as a place for wounded soldiers to recuperate during World War II.

1945 – Winter is given back to Evadne, in terrible condition. She cannot afford to renovate it, but refuses to sell.

1965 – Evadne Burns dies, and Edie inherits Winter but cannot live there.

c. 2010 – Edie dies and leaves Winter to Ros, then aged 30.

Chapter One

In the rear-view mirror, the road was empty for now, wide and black beneath the bright mid-afternoon sky. Peering ahead, I saw darker skies, threatening rain. I hoped fervently it wasn’t an omen. A sign came into focus, telling me the city of Durham was only another fifty miles north. Only another sixty miles to go until I discovered just what sort of a predicament I’d thrown myself into this time. Starting a new life just after my thirtieth birthday, every familiar part of my life hundreds of miles behind me, wasn’t an adventure I’d ever expected or craved. Yet here I was, driving into the uncertainty.

Winter Manor. I let the words drift through my head in the way they had done so many times over the last weeks. They were familiar now, but remained as unsettling as they had been from the beginning. A manor house? Not only a manor house, but a manor house located two hundred miles away from everything familiar to me. My manor house.

Considering it too deeply made it ludicrous. More ridiculous still, I now had all of my worldly possessions packed into my battered silver Ford Fiesta and was heading for the wilds of County Durham—a region I’d never considered, let alone visited—to move in to said newly acquired manor house. Apart from what I hoped were reliable assurances the house had water and electricity, and a wealth of preliminary structural reports I’d tried to wade through, I knew very little about my new home. I’d not even known it existed a month ago.

A few days after my thirtieth birthday in mid-November, a belated and half

-hearted birthday card from my sister had arrived in the morning post through the door of my compact London flat. With it came an intriguing, intimidating letter, summoning me to the offices of a lawyer I’d never heard of. That letter tormented me with curiosity for days. It was all very well informing me I’d been left something in the last will and testament of Miss Edith Burns, and I had to make an appointment to learn the size of the bequest.

What I’d really wanted to know was: who on earth was Miss Edith Burns?

I smiled to myself now as I remembered the kindly lady who lived across the street from my family home in our pretty Hertfordshire village, the house my mother, sister, and I had lived in until I was nearly eleven. Always known to me as Auntie Edie, though she was no relation at all, she had been my surrogate mother, an indulgent grandmother, and an amusing playmate for me in my childhood. My own mother, too busy in her work as a beautician or with indulging my sister—who was five years younger than me and far prettier—had never seemed to have the time for me I’d craved. I’d turned to Auntie Edie instead. I remembered with huge fondness and gratitude her constant supply of lollipops, the horrific lime-green pullover she’d once knitted for me, and the shiny fifty-pence piece she gave to me every birthday.

I’d felt terrible in the lawyer’s office when I’d been informed that Miss Edith Burns was Auntie Edie. I hadn’t forgotten her kindnesses, but I’d not had cause to think of her in many years. The honour that she’d left something to me in her will was momentarily eclipsed by my sadness on realising she had passed away. Eternally a sprightly sixty-something year old in my recollection, I was shocked to learn she had been over eighty when cancer had claimed her. Auntie Edie had been a retired nurse when I knew her. I imagined the bequest would be the adult equivalent of that birthday fifty-pence piece, and I told the lawyer as much.

The lawyer had smiled mysteriously at that point. She informed me Auntie Edie had been born in a small country house, Winter Manor, in County Durham. The property had been in her family for most of the twentieth century but had fallen into disrepair since it was last inhabited in the 1940s. Auntie Edie, having no children, had remembered the little curly-haired child I’d been and left the place to me. I’d also been left most of her money, the result of her lifetime of saving, which was no small sum. The only condition in place required me to oversee the renovation of Winter Manor, returning it to its former glory.

I’d stared open-mouthed and questioned the lawyer’s sincerity. But once she handed me the official documents, I began to believe this strange twist in my fortunes was genuine. Before I’d had a chance to think about it, I’d found myself asking, “Is the house habitable?” I almost hoped she would say no before the idea truly took shape in my mind.

“I believe it is, if you’re prepared to virtually camp to start with,” she replied. “It has electricity and water connected, that much I know. There’s some paperwork, including a full report on what needs to be done and some contact numbers of professionals Edie had already spoken to about taking it on. I think the information’s a few years out of date now, but I don’t suppose much has changed in that time.”

“I could go and live there?” The words had fallen out of my mouth, despite the very reasonable protests my brain tried to interject.

“If you wanted to.”

It was that simple, apparently. At her words, all logical objections took a step backwards, and there was a quickening in my veins that felt something like optimism. I’d looked at the piece of paper in my hands, ignoring the way it trembled with my fingers, and confirmed again this was not a fiction I had dreamed up, it really did inform me Winter Manor was mine. Two hundred miles from everything that still hurt. A place in the middle of nowhere, where my only responsibility would be to a woman I’d loved as a child, and a house full of history. Someone else’s history. For the first time in months I’d seen a path in front of me. Exactly what I had been searching for.

Only now, driving ever closer, the nervous tension was taking hold of me again. What if I failed Auntie Edie? What if I couldn’t deal with such a practical project? What if this didn’t work out, in the same way as everything else in my life lately? I attempted to ignore the doubts. I only knew, for some unshakeable reason, I had to try this. I didn’t have a lot of other options after all.

I sighed and reached out to turn on the radio, hoping to occupy my mind with some talk or music. The haunting electronic notes of “True” by Spandau Ballet filled the car. I turned it off quickly in disgust. That song had way too many memories attached to it, and there were some places I didn’t want my mind to go today. Bittersweet recollection of my early years with Francesca was one of those places. It had been one of the many songs that meant something to us whenever we heard it. For nine years. Now Francesca was gone, and nine years of my life, of loving, of compromise, of sharing my dreams with her, felt wasted.

Tears threatened to blur my vision. I wiped them away quickly and focused again on the road in front of me. I pressed the accelerator to overtake a slow-moving truck and opened the window to let the cold air blow over my face. The roar of the wind, as I drove faster still, obscured everything else. I pushed the accelerator harder. I had no choice now, my decision was made. I’d just have to hope fate was kinder to me than she had been so far in my life. The perfect isolation of Winter Manor beckoned. Right now, it was all I craved.

*

I drew close to my destination at just before three in the afternoon, as the first signs of winter twilight were turning the December sky from pale grey to smoky blue. Following the directions given by the toneless voice of my satellite navigation system, I turned onto a small country lane, edged with hedgerows barren of leaves. I was soon aware of a low stone-built wall running along the side of the road behind the undergrowth to my right. The navigation system, into which I’d programmed the exact GPS coordinates of Winter Manor, instructed me to turn right in one hundred yards. “What the hell are you talking about?” I muttered in return. All I could see were hedges and that low wall. I slowed the car to a crawl as the display counted down the yards. I stopped with a few yards to go and wound my window down. Then I saw the entrance to my new home.

Two stone pillars rose from the tangle of brambles at their base to form ornate and pointed guardians of a pair of wrought iron gates which hung between them. The rusted, swirling metalwork of the gates had once been painted black, but the paint was flaking and faded. Both pillars and gates were intricately laced with ivy, some of it dark, living green, some of it brown and lifeless but still holding the structure in a death grip.

For a long time, I merely sat in my car and stared at the imposing sight. I knew I was in the right place but could barely comprehend the idea of simply opening the gate and going inside. Not only did I feel I would be intruding on what was really somebody else’s property, but I would also somehow be going against the natural order of things. Decay had well and truly set in here, nature was claiming the manmade for herself. Auntie Edie, the last living being with any real claim over this place, had died. What right did I really have to push open that gate, rip the ivy out of the way, and force my way inside? Me versus Mother Nature was a contest unlikely to go my way.

I opened the car door and climbed out. As I felt the ground under my feet I noticed that beneath the weeds of what looked like part of the roadside verge was actually the gravel of a driveway. I approached the gates tentatively and peered between the ornate metalwork and tendrils of ivy. I could see nothing beyond a shadowy avenue of beech trees, which must have once been graceful. With their winter branches bare and after decades of neglect, the trees seemed rather to be guarding the driveway to the house, forbidding figures likely to come to life and tear at my skin and hair, monsters from a horrific fairy story.

I smiled at my runaway imagination and refocused on the driveway beyond the gates. Though it was overgrown, it would still be passable in my car. The view from where I stood offered no clue as to what the house itself looked l

ike, and my curiosity to see it was increasing with every moment. Seeing the state of the gates, I felt a growing trepidation I would find the property in worse condition than I had been led to believe it was in, and I was anxious to reassure myself. The monster trees would not put me off, however hard they tried.

I pushed the gate and was dismayed to find it didn’t budge. I tore at the ivy snaking around the latch and discovered no lock, only a rusted old chain, broken many years ago. I ran my eyes to the base of the gates and discovered the problem at once: there was a bolt, dropped down and stuck in the ground. I bent and tried to force it up. It creaked, but resisted me. I straightened, and brushing the rust from my hands, went to my car and retrieved a can of WD-40 from a box on the back seat. I’d bought it, along with some initial supplies, because some vague memory of my father’s garage workshop, from the occasional weekends I spent with him after my parents’ divorce, had told me it was a magical fix-all substance. Had to be worth a try. I shook the can and squirted some of the light oil onto the stubborn bolt. While it trickled through the rusty lock, I stowed the can in the car. I returned to the gate and tried again. I pulled with both hands this time. Just as I thought I’d failed in my attempt, the bolt slid free of the ground and both gates shuddered and groaned.

Disproportionately elated by my first practical success at Winter Manor, I pushed the gates. The ivy strained against me, still trying to bar my entry. I took a deep breath and pushed harder. The sound of stems and leaves tearing and releasing their hold gave me unexpected satisfaction. The gates scraped along the ground, and the hinges sounded ready to give up, but still, they opened. It was the first thing I’d achieved in months.

Fragile Wings

Fragile Wings The Locket and the Flintlock

The Locket and the Flintlock Ghosts of Winter

Ghosts of Winter